Special Renewable Energy Credits

Generate Benefits for People and Planet

Generate Benefits for People and Planet

Azurent is pleased to offer ‘social impact’ RECs that reward disadvantaged communities with support for new sources of clean and reliable energy, job development and added revenue to fund local infrastructure projects and improve quality of life.

Diverse and Wide-Ranging Sources

Azurent’s renewable energy credits (RECs) come from power projects worldwide, all with environmental attributes that offset the greenhouse gas emissions linked with use of conventional fossil-fueled electricity. However, certain RECs carry an added benefit. These “social impact” RECs give back to disadvantaged indigenous groups living in the vicinity of wind, solar and small hydro projects. In addition to supporting projects that deliver clean and reliable power, these RECs reward locals with an array of benefits, including jobs, new revenue to fund community projects decided locally and infrastructure projects such as roadways and public structures.

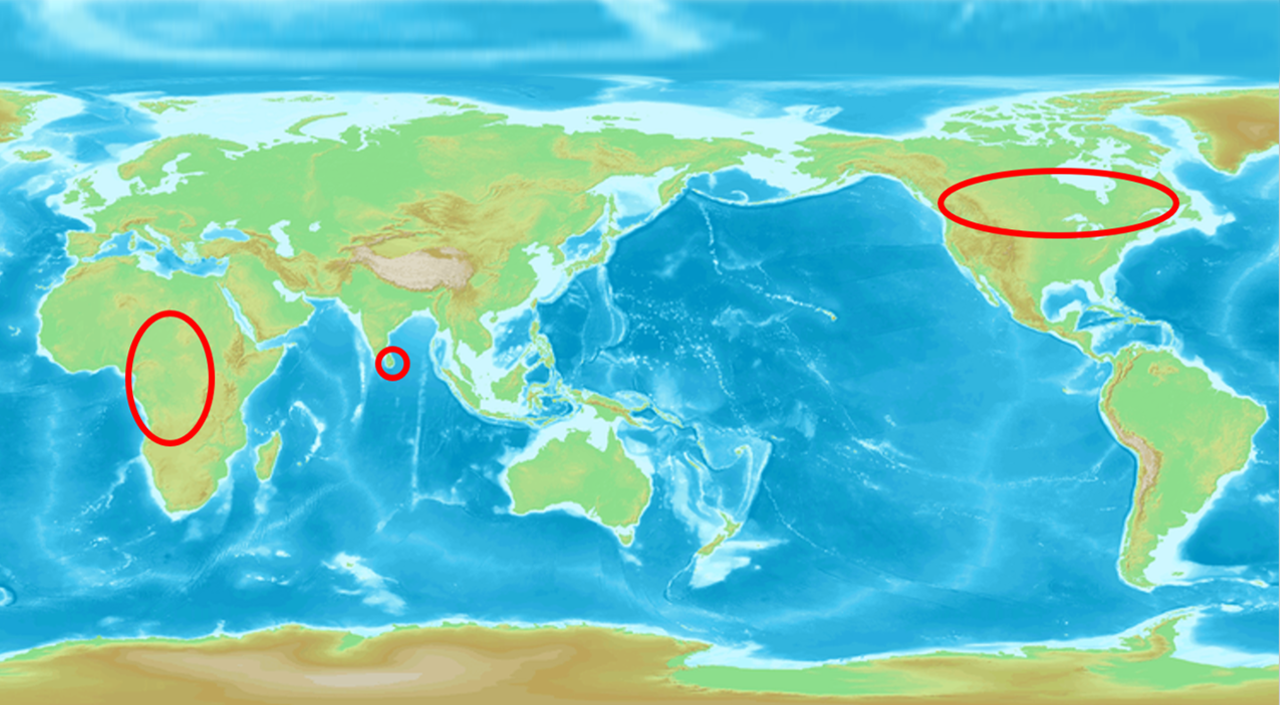

Project locations are worlds apart. Sri Lanka is a lush tropical island nation near the equator and south of India. Canada is subarctic. The 11 nations of the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) vary from rainy to arid, from highlands to savannas. Azurent has contracted with each of the three source areas to market their RECs. Currently, the company is actively marketing credits from Sri Lanka and Canada. An exclusive agreement signed with ECCAS will lead to marketing of credits from newly built projects there.

Certain Azurent RECs benefit indigenous people of central Africa, Canada and Sri Lanka, an island nation off the southern tip of India.

Low-Impact Hydro from Tropical Sri Lanka

This tropical island nation still relies on imported fossil fuels but has committed to energy self-sufficiency by 2030 and 100% renewable power sources by 2050. Azurent supports small hydro projects in the mountainous interior to help meet both goals.

Sri Lanka’s mountainous and rainy south central interior is ideal for small run-of-the-river hydro power projects.

Run-of-the-River Hydro

Azurent is the exclusive marketer of RECs from eight small hydro sites in south central Sri Lanka, which features mountains, steep river canyons and heavy rainfall. All projects are run of the river, simply using the natural flow of streams to generate power and then returning water to the stream after generating power. Electrical output displaces the national utility’s highest cost electricity output from imported coal or fuel oil, reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The projects featured below were developed on a scale suitable for meeting local community and economic needs. A significant portion of REC sales funds project operations and maintenance activities and contributes to a community fund.

Social and Economic Benefits

– Jobs for locals, including operators, laborers, security, etc.

– New roads for motorable access to area homes, replacing footpaths

– Revenue sharing with community for projects local residents choose

– Upgrades to power distribution lines to improve reliability and reduce outages

– No atmospheric, noise or other pollution to affect health and well-being

– Displaced high-cost power from projects burning imported fuels

– Support for Sri Lanka’s goal of energy independence

– Supply to meet growing demand for electricity and fuel economic growth

SRI LANKA PROJECT PROFILES

Alupola Small Hydro

Badulu Oya Small Hydro

Ellapita Ella Small Hydro

Glassaugh Small Hydro

Hapugastenna I & II Small Hydro

Hula Ganga I & II Small Hydro

Magal Ganga Small Hydro

Mandagal Oya Small Hydro

Renewable Power on Native Lands

Throughout Canada, indigenous groups are working with the private sector and governments to undertake renewable energy projects. Their goals: minimize reliance on diesel generators, offset high electricity costs and create new revenue.

Aishihik Creek, Yukon Territory

Bow Lake Wind Farm, Ontario

Small Hydro and Wind Power

Native Canadian groups have been significantly involved in more than 150 renewable energy projects nationwide. Their participation ranges from impact benefit agreements to direct and full ownership of small hydro or wind projects. Typically, these projects supply electricity to utility power grids, reducing reliance on coal, gas and diesel fuel. This indigenous commitment shows no sign of slowing down, as project development continues.

Most indigenous renewable energy projects share these features:

– Project developed on traditional tribal territory

– Partnership with energy development companies or utilities

– Operation as a limited partnership and independent clean energy business

– Minimum of one and sometimes several indigenous partners

– Power sold to utility electric grids

– Frequent development support from government groups

– Construction by way of long-term commercial financing

Azurent has established relationships with numerous indigenous groups in most of the Canadian provinces and territories for the sale of their RECs. A substantial portion of the revenue earned is shared with those communities to fund projects as determined by local leaders.

Social and Economic Benefits

– Greater community pride and affirmation of indigenous rights and territory

– Improved relationships with project partners, government and utilities

– Indigenous employment during construction and throughout project operation

– New revenue for infrastructure upgrades, education, housing, etc.

– Increased electricity reliability and in some cases new electric heat for homes

– Displaced high-cost power from projects burning imported fuels

– Reduced risk from the transportation, storage and use of diesel fuel

– More electricity supply to meet growing demand and fuel economic growth

CANADA PROJECT PROFILES

Aishihik Small Hydro Facility

The Aishihik project is on the ancestral lands of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations (CAFN). In this subarctic climate, with an average annual high of just 36°F (2°C), winters are made more manageable by the project’s three generators. They produce about 25% of Yukon’s annual electricity supply. In winter, output climbs to 40-50%, with enough power for up to 12,500 homes.

Nearby hydro facilities may be larger, but their effective capacity dips nearly in half during the coldest months because of reduced water flow, while Aishihik operates at top capacity year-round. It uniquely stores energy in the summer when demand is low for use in the winter when demand is high and can also store energy during wet years for use in dry years. The project uses natural water storage at Sekulmun, Aishihik and Canyon Lakes.

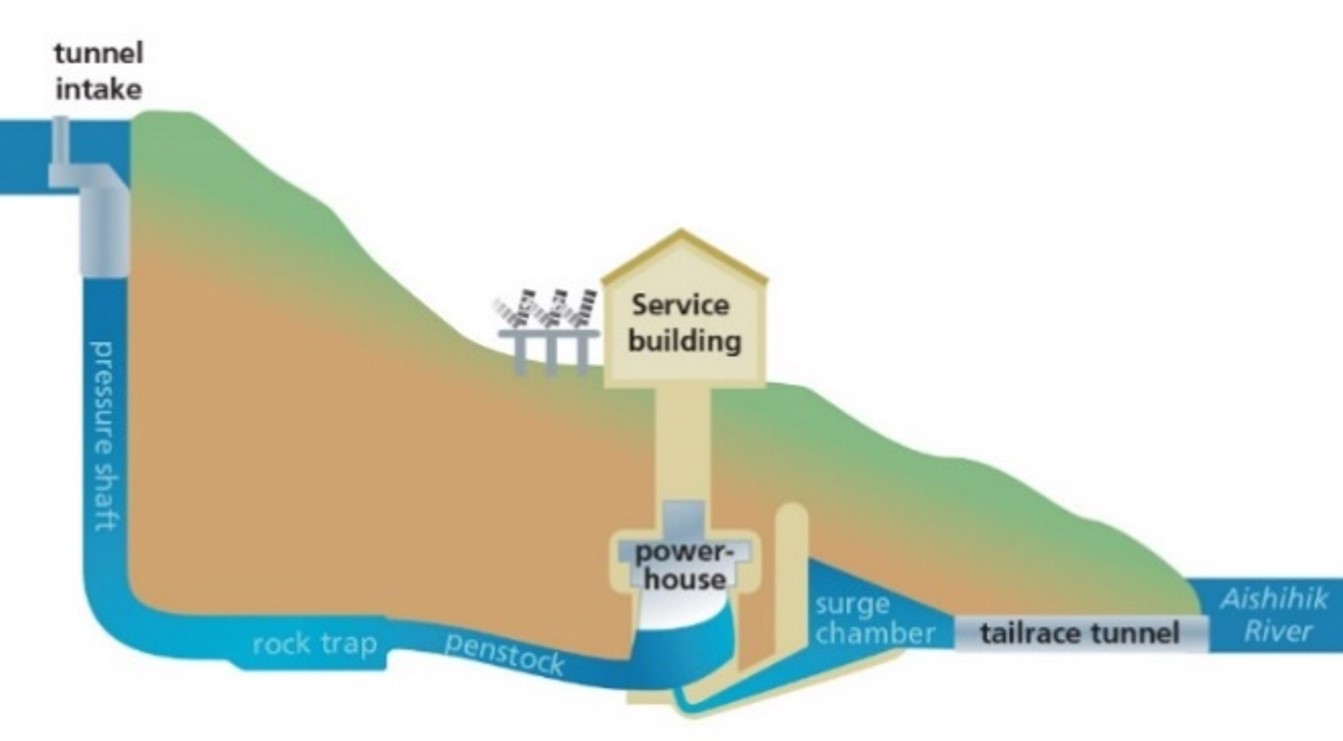

Even more unique, Aishihik’s generators are located 361 feet underground. Aishihik is the first underground power plant north of the 60th parallel in the western world. Aishihik River water flows along a 3.6-mile canal to the tunnel intake, dropping 574 feet to a pipeline that’s nearly 3,000 feet long. The water enters the station 361 feet below the surface. After powering the turbines, water returns through a tailrace tunnel to the West Aishihik River.

Without Aishihik’s reliable output, Yukon electricity consumers would get their power from high-cost thermal generators using diesel fuel or liquefied natural gas. These are the fossil fuels that Yukon Energy must draw from when hydro is not available and winter load is high. Demand for electricity in cold months continues to grow, as many new Yukon homes are electrically heated rather than dependent on diesel generators. Built to provide reliable power for a growing population and a large lead-zinc mine in central Yukon, Aishihik continues to be essential for meeting current demand and future growth.

Aishihik’s unique powerhouse is underground. Water drops 574 feet to the intake, travels 3,000 feet and enters the station 361 feet below the surface. Water exits via a tailrace tunnel and returns to the West Aishihik River.

A 3.6-mile canal leads to generators, sited underground for reliable power production during subarctic winters.

Champagne and Aishihik First Nations homelands cover a vast area surrounding Aishihik Lake in Yukon.

Truro Heights Community Wind

The Mi’kmaq have taken control of their energy supply by developing multiple wind projects. Inspiration came from Nova Scotia’s high electricity prices, heavy dependence on imported coal for power generation and a need to grow their economy while protecting the environment. Today, the Mi’kmaq are generating more electricity than their 13 communities consume. Electricity not used by the Mi’kmaq is sold to Nova Scotia Power through a 20-year power purchase agreement. Revenue is applied to project debts, with remaining funds divided among the 13 Mi’kmaq bands to meet locally defined needs.

The Mi’kmaq now have four wind projects in Colchester County, Nova Scotia: 6.5-MW Millbrook, 4.4-MW Truro Heights, 4-MW Whynotts and 6.6-MW Amherst. Their combined generating capacity is enough to power 4,800 homes. Beaubassin Mi’kmaq Wind Management, a company owned by the 13 band councils in Nova Scotia, manages the projects.

First Nations companies were hired when possible for construction and security jobs, and some continue working on operations, maintenance and security crews. Band members were invited to apply for a wind turbine technology course, and several took the opportunity to study at a wind training facility in Prince Edward Island. Long-term economic benefits to the Mi’kmaq also include tax revenue and creation of a community sustainability fund.

These projects support Nova Scotia’s plan to gradually transition the province to local renewable energy sources, including wind, tidal and solar technologies. Adopting greener, more affordable sources of electricity lessens Nova Scotia’s dependence on imported fossil fuels, the dominant electricity source today. The province is made less vulnerable to rising energy prices and is able to keep more revenue local.

The Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia now generate more electricity than their communities consume. Truro Heights has displaced high-cost power and use of imported coal.

Snare Cascades Small Hydro

The Dogrib band get their name from a myth about a hero who changed from a dog to a person. The Dogribs continue to transform, going from near decimation in the mid-1800s to a growing population, securing the first combined self-government agreement and First Nation land claim in the Northwest Territories, and inking a deal for the world’s first native-run power project.

Dogribs signed a $115 million deal to finance, build and own two small hydro projects in the Great Slave Lake area. The tribe formed the Dogrib Power Corporation to own the projects, while the Northwest Territories Power Corporation (NTPC) would rent them. Every phase of the project – such as construction, engineering and environmental management – was under Dogrib control. The Dogrib provided 15% of the cash needed and financed the remainder.

Today, the Dogrib’s Snare Cascades small hydro project is delivering significant recurring revenue and affordable, clean energy to power through brutal winters. Without the unit, NTPC would call on diesel generators to meet demand at a cost of about $50,000 in Canadian dollars per week.

When this most northerly hydro system in Canada was first developed in 1948, Yellowknife was evolving from a primitive, raucous pioneer settlement to an orderly town. Reliable power paved the way for modernization. Construction was challenging and complicated by weather. Permafrost turned to sticky, slippery mud by the Arctic sun’s intense rays, hampering progress. Transportation of incoming construction and installation equipment presented an even greater obstacle. The remote site is accessible by airplane from April through November and via ice road truck during the winter months, when daytime temperatures of -22°F are common. The Snare Hydro project extended the knowledge of cold-region engineering and construction from the Alaska Highway and Canol Pipeline projects to water resource engineering projects.

The Dogrib nation financed, built and now fully owns Snare Cascades, the first native-run project of this type anywhere. The record deal set the Dogrib on the path to controlling its own destiny and securing ownership of homelands.

Snare Cascades is located 472 miles north of Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories. Reliable power has met the needs of area gold mines and helped modernize the once primitive and raucous settlement.

Bow Lake Wind Farm

The Batchewana First Nation of Ojibways is an Ojibway First Nation in northern Ontario. Their traditional lands run along the eastern shore of Lake Superior, from Lake Superior to Batchawana Bay to Whitefish Island.

Here in Canada’s Algoma District, close to the eastern edge of Lake Superior, 50 miles northwest of Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan and within the original reserve of the Batchewana, the Bow Lake Wind Facility has been churning out clean renewable energy since 2015. The 58-MW project, with its 36 1.2-MW turbines, is the culmination of a partnership between the Batchewana and BluEarth Renewables, one of the largest economic partnerships involving a First Nation and a wind energy developer in Canada. The joint-venture project is owned by the Nodin Kitagan Limited Partnership. The Batchewana know and refer to the project as Chinodin Chigumi Nodin Kitagan. Electricity generated by the project is being sold to the Ontario Power Authority under a 20-year contract.

Both participants in this joint venture share in the project’s economic benefits, risks and costs. The Batchewana contributed $8 million of the band’s own funds to launch the project. In return, 80 Batchewana citizens gained employment during construction and later performed operations and maintenance tasks. Recurring revenue generated from the wind farm has been directed to Batchewana housing, infrastructure, health care, cultural programs and governance. Annual revenue for Batchewana is an estimated $2 million over a 20-year period, an important contribution to Batchewana households in this economically depressed area

Headquartered in Calgary, BluEarth Renewables is a private company focused on renewable energy development on a commercial scale. BluEarth is committed to developing projects in partnership with indigenous groups in a way that balances social value, environmental protection and principles of shared revenue.

The Batchewana nation entered a joint venture to develop Bow Lake Wind Farm, also known as Chinodin Chigumi Nodin Kitagan. The tribe contributed $8 million to launch the project, creating 80 new jobs for the community.

With a location overlooking Lake Superior, the Bow Lake project represents one of the largest economic partnerships between a First Nation and a wind energy developer in Canada.

Mayo B Small Hydro

The Na-Cho Nyak Dun are called the Big River People because their ancestors camped, hunted and trapped along the Stewart River they called the Na-Cho Nyak, or Big River. Appropriately, their descendants today are self-governing and have full indigenous rights 1.2 million acres along the Stewart and the town of Mayo. This is the location of Mayo B, built on tribal lands newly ceded to this First Nation. Operation of Mayo B provides long-term economic rewards for this small, formerly nomadic band.

Water power, gold and silver are among the natural resources found in this inhospitable northern outpost. Gold was first discovered in 1883, then silver in 1903. In the 1880s, as many as 100 men a year worked the gravel bars of the Stewart River. It came to be known as “Grubstake River” because a miner could always find enough gold there to cover his costs for a season. While it was the search for gold along the Stewart River in 1883 that first brought outsiders in any number to the region, it was the discovery and subsequent development of massive silver deposits that gave the area its name, character and stability. When the first silver claim was staked in 1903, the settlement of Mayo sprung up and mining began in 1913. By the 1950s, the area became Canada’s second largest producer of silver and the fourth largest worldwide.

The Keno Hill Mine at Elsa, 28 miles north of Mayo, needed electricity for its silver mining operations, and so the 5-MW Mayo A project was built in 1951 to meet the need. Decades later, as the local population grew even as mining operations had begun to wane, two 5-MW Mayo B units were added 2.3 miles down the river. This time, however, the small hydro project would be built on land owned by the newly independent Na-Cho Nyak Dun, and this small band of just 600 or so people would be the beneficiary for many years to come.

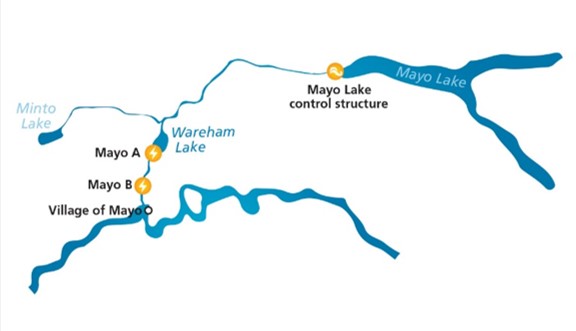

To supply Mayo B, water flows through a control structure on Mayo Lake, a small dam at Wareham Lake and then a 2.3-mile buried steel pipe. The water drops 210 feet to the Mayo B turbines, then exits into the Stewart River.

The Mayo River supplies water to the two generating units at the Mayo B dam, which generates power and long-term economic rewards for the self-governing Na-Cho Nyak Dun nation.